You’re drowning in lecture slides. Your notes from Intro to Psychology are somewhere in a Google Doc you can’t find. That brilliant point your professor made three weeks ago? Vanished. And exam season is approaching fast.

Sound familiar? You’re not alone. Most students treat note-taking as digital hoarding—frantically capturing everything during class, then never looking at it again until the night before an exam. The problem isn’t your memory or intelligence. It’s your system.

A second brain for students transforms this chaos into clarity. It’s not just another note-taking app or study hack—it’s a complete methodology for organizing your academic life so that every lecture, reading, and idea becomes a building block for better grades. In this guide, you’ll learn how to adapt the proven Second Brain system specifically for university life, turning passive note-taking into active learning.

Why Traditional Note-Taking Fails in the Digital Age

Let’s be honest about what most student “organization systems” actually look like:

Random Word documents titled “Notes 10/15” scattered across your desktop. Lecture PDFs downloaded to your Downloads folder and promptly forgotten. Highlights in textbooks you’ll never review. Bookmarks saved “to read later” that pile up into digital guilt. Physical notebooks for some classes, digital notes for others, with no unified way to connect ideas across subjects.

The digital age promised to make learning easier, but it delivered information overload instead. You have more access to knowledge than any generation in history, yet that knowledge sits in disconnected silos. When exam time arrives, you waste hours hunting for notes rather than actually studying them.

Traditional note-taking fails because it’s designed for capture, not retrieval. It assumes you’ll remember where you saved that critical concept or which document contains the citation you need. Spoiler alert: you won’t.

A second brain solves this by organizing notes around when and how you’ll actually use them—not by arbitrary categories like “Fall 2024 Classes” or “Random Ideas.”

The Second Brain for Academia: Your P.A.R.A. Setup for a Semester

The foundation of an effective second brain system is the P.A.R.A. method—a four-folder structure designed for actionability. Here’s how to adapt it specifically for student life.

Projects: Your Courses and Assignments

Projects are short-term efforts with clear deadlines and deliverables. In academia, these are your active courses and specific assignments.

Each course gets its own project folder with a clear naming convention:

[P] HIST 101 - World Civilizations[P] CHEM 201 - Organic Chemistry[P] ENG 305 - Critical Analysis Paper

Within each course project, organize by type:

- Lecture Notes: Date-stamped notes from each class session

- Reading Notes: Highlights and summaries from textbooks and articles

- Assignments: Specific papers, problem sets, or projects

- Study Materials: Exam prep notes, practice questions, flashcards

The key insight: your Chemistry midterm prep is a project because it has a deadline (exam day) and a deliverable (your grade). Once the exam passes, the entire folder moves to Archives.

Areas: Your Academic Responsibilities

Areas are ongoing responsibilities without finish lines. For students, these represent your broader academic life:

[A] Academic Career Planning– Resume, internship applications, grad school research[A] Financial Aid & Scholarships– FAFSA info, scholarship deadlines, budget tracking[A] Student Organizations– Club meeting notes, leadership responsibilities[A] Professional Development– Skills you’re building, networking contacts

Areas differ from Projects because they never “complete.” You’ll always be managing your academic career or tracking finances—these responsibilities persist across semesters.

Resources: Your Personal Library of Knowledge

Resources are topics of genuine interest that transcend specific courses. This is where interdisciplinary connections happen:

[R] Cognitive Psychology Concepts– Fascinating ideas about how learning works[R] Climate Change Research– Articles and data you’re collecting over time[R] Philosophy of Science– Big questions that came up across multiple classes[R] Study Techniques That Actually Work– Meta-learning strategies

The Resources folder is your personal Wikipedia—a growing knowledge base built from all your courses. When a concept from your Biology class connects to something from Philosophy, both notes reference each other here.

This is where the real magic of organizing university notes happens: you stop thinking in isolated courses and start building genuine understanding across disciplines.

Archives: Completed Classes and Old Projects

Archives contain inactive material you’re finished with but want to preserve:

[Z] Fall 2024 Semester– All completed courses from that term[Z] Sophomore Year Projects– Old papers and assignments[Z] Completed Electives– Classes you’re done with but might reference

Archiving keeps your workspace clean without deleting potentially valuable information. When writing your senior thesis, you might need to reference that paper you wrote freshman year—it’s preserved in Archives, not cluttering your active Projects.

Student Pro Tip: At the end of each semester, do a 30-minute “Archive Sprint.” Move all completed course folders to Archives, extract any evergreen concepts to Resources, and start the new semester with a clean slate.

Using C.O.D.E. to Turn Lectures into A+ Essays

The P.A.R.A. structure tells you where to file notes. The C.O.D.E. workflow tells you how to process them. This is the best note taking system for college because it transforms passive transcription into active learning.

Capture: More Than Just Typing

Capturing is the art of saving what resonates without breaking your flow. During lectures, don’t try to transcribe everything word-for-word—that’s stenography, not learning.

Instead, capture:

The professor’s exact words when they say: “This will be on the exam,” “This is the most important concept,” or “Students always miss this point.” Use quotation marks and highlight these in red.

Your own questions and confusion: When something doesn’t make sense, write [?? Why does this contradict what we learned last week?] Your confusion is valuable data for what to clarify during office hours.

Connections to other knowledge: When today’s Chemistry lecture suddenly makes that Biology concept click, write [→ This explains the cell membrane permeability from BIO 101] These links are gold for exam preparation.

Citations and sources: Whenever a professor mentions a study, book, or researcher, capture the full reference immediately. Future you writing a research paper will be grateful.

Visual information: Take photos of diagrams, equations, or whiteboard work. Embed them directly into your digital notes with a caption explaining why they matter.

The goal isn’t comprehensive documentation—your lecture slides already do that. The goal is capturing understanding as it happens.

Organize: Filing for Fast Retrieval

Organizing should take seconds, not minutes. The beauty of P.A.R.A. is that every note has an obvious home.

After each lecture, ask one question: “When will I use this?”

- If it’s for the upcoming midterm → File in

[P] PSYCH 201/Lecture Notes - If it’s a general concept you’ll reference across courses → File in

[R] Research Methodology - If the course is over → Move to

[Z] Archives/Spring 2024

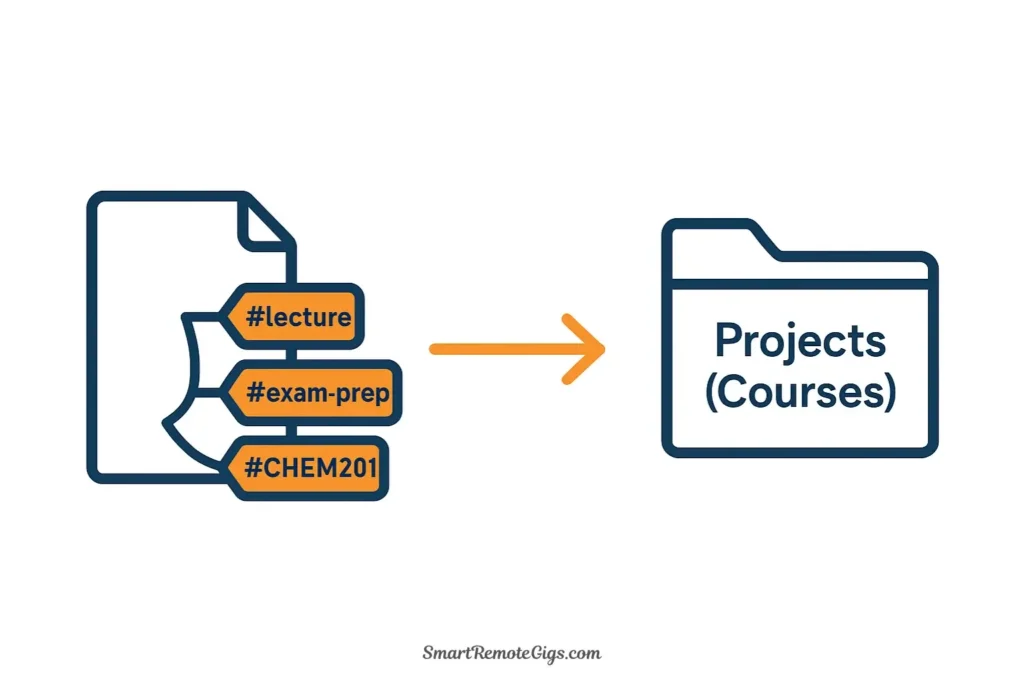

Use consistent tagging for rapid filtering:

#lecturefor class session notes#readingfor textbook and article highlights#assignmentfor papers and projects#exam-prepfor study materials

When you’re studying for finals, searching #exam-prep #CHEM201 instantly surfaces every relevant study note. This is digital note organization for exams that actually works under pressure.

Distill: The Art of “Progressive Summarization” for Studying

This is where most students fail: they capture everything but never process it. Distilling transforms raw notes into study-ready material.

Progressive Summarization works in layers:

Layer 1 – Bold the important sentences: During your first review (ideally within 24 hours of the lecture), bold 10-20% of your notes—the sentences that capture the core concepts.

Layer 2 – Highlight the key phrases: A week later, when reviewing for an exam, highlight 10-20% of the bolded text—the specific terms, definitions, or principles you absolutely must remember.

Layer 3 – Write an executive summary: At the top of the note, write 2-3 sentences summarizing the entire lecture in your own words. This is your “TL;DR” for last-minute review.

Here’s what progressive summarization looks like in practice:

📝 Biology 201 – Lecture 12: Cellular Respiration

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Cellular respiration converts glucose into ATP through three stages: glycolysis (cytoplasm), Krebs cycle (mitochondria), and electron transport chain (inner membrane). Net yield: 36-38 ATP per glucose.

Full Notes (Layer 0):

Cellular respiration is the process where cells break down glucose molecules to produce ATP, which is the energy currency of the cell. The process happens in three main stages. First is glycolysis, which occurs in the cytoplasm and breaks glucose into pyruvate. Then the Krebs cycle happens in the mitochondrial matrix. Finally, the electron transport chain in the inner mitochondrial membrane produces most of the ATP. The net yield is approximately 36-38 ATP molecules per glucose molecule.

Bolded Key Sentences (Layer 1):

Cellular respiration is the process where cells break down glucose molecules to produce ATP, which is the energy currency of the cell. The process happens in three main stages. First is glycolysis, which occurs in the cytoplasm and breaks glucose into pyruvate. Then the Krebs cycle happens in the mitochondrial matrix. Finally, the electron transport chain in the inner mitochondrial membrane produces most of the ATP. The net yield is approximately 36-38 ATP molecules per glucose molecule.

Highlighted Critical Terms (Layer 2):

Cellular respiration produces ATP through glycolysis (cytoplasm), Krebs cycle (mitochondria), and electron transport chain (inner membrane). Net yield: 36-38 ATP per glucose.

When exam day arrives, you can review just the highlighted phrases for a quick refresh, or dive into the full notes if you need deeper understanding. This layered approach is the PARA method for students in action—notes organized by how you’ll actually use them.

Express: From Notes to Outlines to Final Drafts

Expression is where learning becomes visible. A second brain isn’t a storage system—it’s a creativity engine.

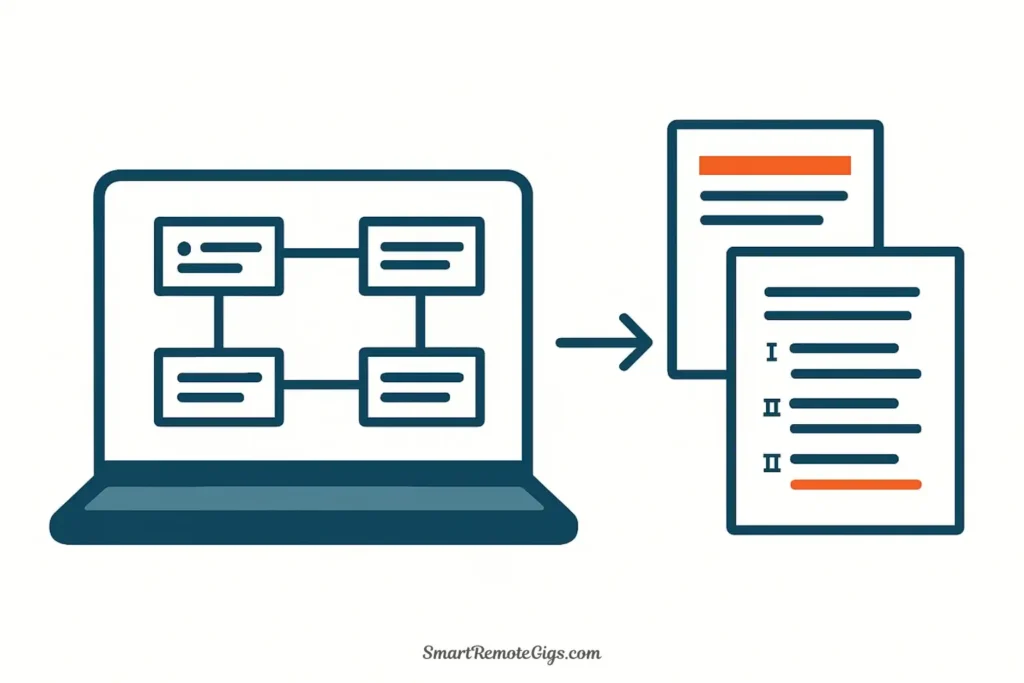

For research papers, your distilled notes become your outline:

- Search your system for all notes tagged with the paper’s topic

- Review the executive summaries to find the strongest arguments

- Copy the highlighted key phrases into a working document

- Organize them into a logical structure—your paper’s skeleton

- Write connective tissue around the evidence you’ve already collected

You’re not starting from a blank page. You’re assembling pre-processed insights into a coherent argument.

For exam preparation, expression means creating study materials:

- Convert your highlighted notes into flashcards (use tools like Anki)

- Write practice exam questions based on your executive summaries

- Teach the concepts to a friend or study group—teaching is the ultimate form of expression

- Create concept maps linking ideas across different lectures

Every time you express your knowledge—write a paper, answer a practice question, explain a concept aloud—you deepen your understanding. This is active learning, and it’s why students with a second brain consistently outperform those who just re-read their notes.

Recommended Tools for the Student Budget

The best second brain tool is the one you’ll actually use, but choosing from the dozens of available options can be overwhelming. To help you make the right choice, we’ve tested and ranked all the top contenders in our definitive guide to the Best Note-Taking Apps of 2025.

For students specifically, a generous free plan and features that support academic work are crucial. With that in mind, here are the top options that fit the student budget:

Notion (Free for Students)

- Best for: All-in-one organization with databases, calendars, and templates

- Strengths: Beautiful visual interface, easy to share notes with study groups, robust free education plan

- Ideal student use case: Managing both notes and task lists in one place

- See our complete Notion setup guide for students

Obsidian (Free Forever)

- Best for: Linking ideas across courses and building a long-term knowledge graph

- Strengths: Lightning-fast, works offline, plain-text files you own forever

- Ideal student use case: Philosophy, history, or any field where connecting ideas matters more than pretty formatting

- Learn how to set up Obsidian for academic work

Zotero (Free and Open Source)

- Best for: Research paper citation management

- Why it’s essential: Automatically generates citations, stores PDFs, integrates with Word/Google Docs

- Pro tip: Use Zotero alongside Notion or Obsidian—it handles citations while your second brain handles ideas

- Download Zotero here

Apple Notes or Google Keep (Free)

- Best for: Absolute beginners who want zero setup friction

- Limitations: Basic organization only, but better than scattered documents

- When to choose this: If you’re skeptical about the system and want to test it with minimal commitment

Bonus Tool: Otter.ai (Free Tier)

- Transcribes lectures automatically, perfect for classes where you can’t keep up with typing

- Export transcripts to your second brain for distillation and organization

Budget Tip: Start with completely free tools (Obsidian + Zotero) to build the habit. Upgrade to paid features only after you’ve proven the system works for you. Your grades will improve because of the methodology, not expensive software.

For a detailed comparison of the top options, read our Notion vs. Obsidian breakdown.

Your First Week Action Plan

Ready to get started? Here’s your concrete roadmap for the next seven days:

Week 1 Checklist:

- ☐ Day 1: Choose your tool (Notion or Obsidian recommended)

- ☐ Day 1: Create your 4 P.A.R.A. folders (Projects, Areas, Resources, Archives)

- ☐ Days 2-5: Capture notes from at least 3 lectures using the C.O.D.E. capture tips

- ☐ Day 3: Practice filing—organize your captured notes into the right P.A.R.A. folders

- ☐ Day 6: Try progressive summarization on one set of lecture notes

- ☐ Day 7: Schedule your first 30-minute weekly review for Friday afternoon

Success metric: By the end of week 1, you should have notes from multiple classes organized in one system, with at least one set distilled and ready for studying.

Your Academic Success Starts Today

A second brain for students isn’t about collecting more notes—it’s about thinking better. It transforms study from a passive chore (re-reading the same highlighted textbook for the third time) into an active process of knowledge creation.

The students who consistently earn top grades aren’t necessarily smarter. They have better systems. They capture strategically, organize intuitively, distill ruthlessly, and express regularly. Their notes work for them, surfacing the right information at the right moment.

You already spend hours taking notes, reading, and studying. A second brain simply ensures that time investment compounds. Every note you take this semester becomes a resource for next semester. Every connection you make between concepts deepens your understanding. Every paper you write draws from a growing library of processed insights.

Start today by creating four P.A.R.A. folders for your current semester. Open whatever note-taking app you already have (even if it’s just Apple Notes). Create folders labeled:

- Projects

- Areas

- Resources

- Archives

Then capture one thing: today’s lecture notes, a reading assignment, or a paper deadline. File it in the appropriate folder.

That’s it. You’ve started building your second brain.

Your future self—the one acing exams, writing papers in half the time, and actually remembering what you learned—will thank you.

What will you capture first?